Weaving Panelists Find a Common Thread

Left to right: Susan Gangsei, Amy Shebeck, Jacob Moore, Robbie LaFleur, Lisa Torvik

On April 15th, the North Suburban Center for the Arts hosted an artist panel featuring four weavers included in the exhibition, Weaving the North: Robbie LaFleur, Jacob Moore, Amy Shebeck, and Lisa Torvik—Jes Reyes was also invited to participate but unable to attend. The event was moderated by Susan Gangsei, former artist-in-residence for the NSCA and tapestry weaver, involved in the American Tapestry Alliance and Tapestry Weavers West.

“…the same set of tools that we all work with, and yet the diversity of outcome that we can get from that…”

Lisa Torvik shows audience members the transparency technique in her piece Horda 3rd Gen.

Discussion of process and inspiration filled the room —Gangsei began by asking each weaver how they got started and answers ranged from training decades ago (both LaFleur and Torvik studied weaving at Valdres Husflidskole in Fagernes, Norway) to more recent explorations, earning the Weavers Guild of Minnesota a few shoutouts.

A sense of curiosity and deep care for the medium’s potential echoed around the table, regardless of the years spent at the loom.

Later on, this notion was solidified when an audience member asked about upcoming projects and everyone chimed in enthusiastically with plans for not just one project on the horizon, but many.

Audience members learned more about the works on the walls, including Amy Shebeck’s Veil and Raft, both of which employ natural dyes including cochineal, madder, and indigo. For Shebeck, the process begins long before the yarn meets the loom as each skein must be prepared, dyed, washed, and wound—once after drying and another time around the loom to become the warp.

Shebeck’s process embraces the lack of predictability inherent in natural dyeing and even utilizes mordant (a fixitive for dye) to find unique color placements through chance encounters, as seen in Veil. The gradient of blue, derived from indigo, is spliced by pops of fuschia from areas overdyed with cochineal.

Indigo is a dye derived from plants, primarily extracted from the leaves of Indigofera tinctoria. Most commonly, indigo is used to dye denim. Cochineal (Dactylopius coccus) is a dye created with insects—yep, that’s right—bugs. These bugs, cochineal, are found on prickly pear cactus in Mexico, Central and South America, and few other places globally. Depending on how you mix this dye, it can yield a fiery orange to a deep purple hue.

Shebeck’s work manipulates the technical aspects of weaving to uncover optical effects, through dye but also irregular threading and treadling.

Warp and weft, common parlance in a weaver’s vocabulary, refer to the direction of the fiber in the composition. Warp refers to the yarns that run lengthwise and remain stationary on the loom. These fibers undergo a great deal of tension, so weavers often select strong fibers like wool, cotton, or rayon. Weft refers to the fibers that run horizontally, woven in between the strands of the warp. Since these fibers are not wound tightly around the loom, weavers can experiment with weft fibers—nearly anything is fair game, from silk to shoelaces.

Panelists shared the most uncommon items they’ve used to weave—with answers of tree branches, cow gut, and pages from a (damaged) archival text surprising audience members.

In some cases, like LaFleur’s Burn 2020, unconventional materials find their way into the work in surprising ways.

Burn 2020, a flat-weave tapestry mostly made from Norwegian wool, features a bright bonfire with flecks of silk that catch the light and resembles the flame’s white hot glow.

On the back of the tapestry, affixed to the mounting bar, LaFleur pasted several newspaper headlines from the moments during which she wove the tapestry. As process photos show, and the title suggests, LaFleur’s piece is a time capsule of the difficult moments of 2020 as the COVID-19 pandemic began.

But the memory itself, is a moment of respite. Inspired by a week in the woods with her family, the first since isolation began, the tapestry gives a sense of warmth and family. But the iconography of the flames also offers a second meaning—one of isolation, loss, and grief and the deep desire to burn the year away.

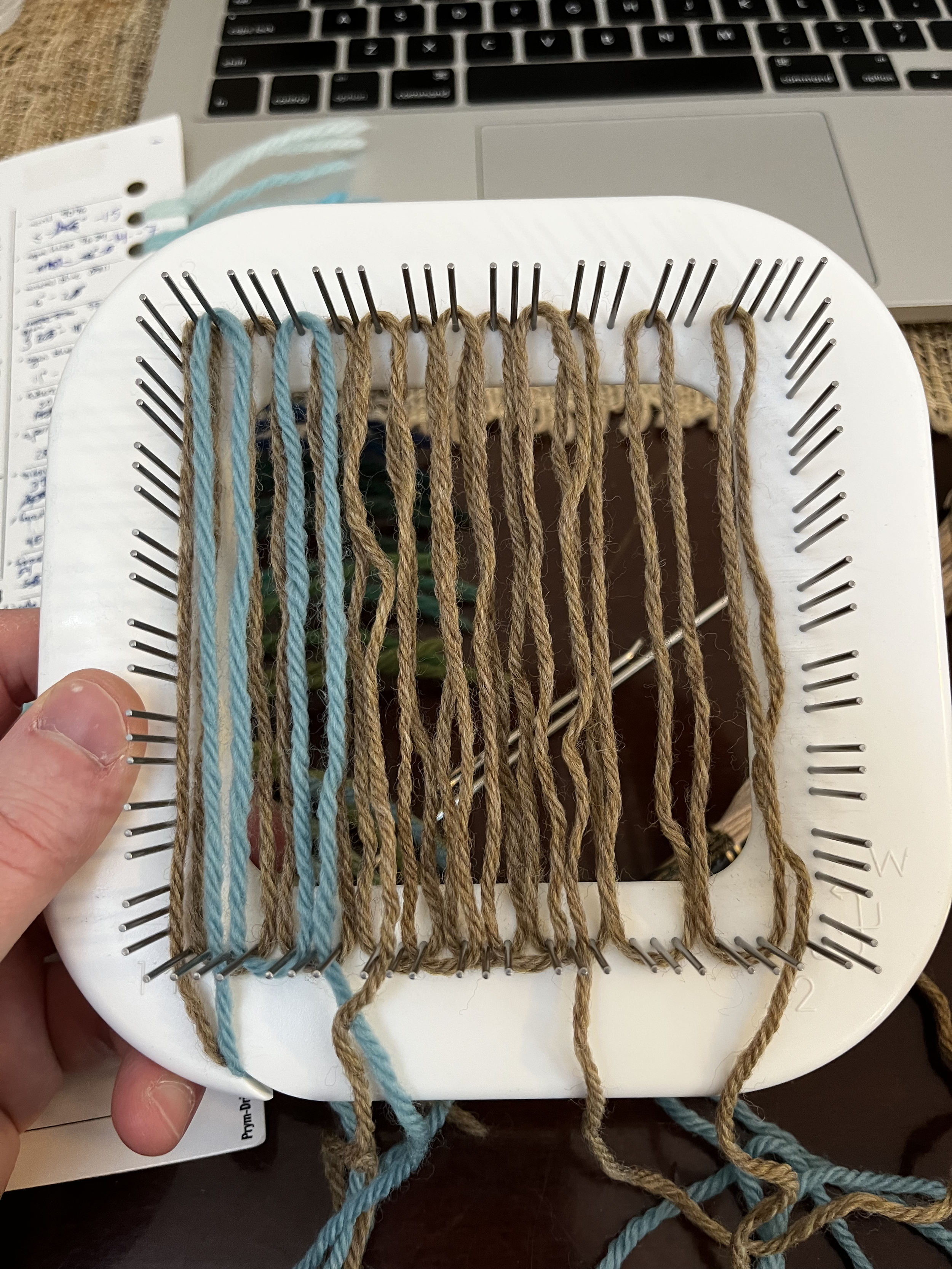

The weavers’ stories highlighted how textiles can be markers of time and memories. Jacob Moore’s 2022 - A Year in Color captures the temperatures recorded by the MSP airport weather station each day of 2022. Though it is an enormous piece, measuring nearly six by seven feet, Moore’s blanket was completed on the tiniest scale, day by day. Moore used a 4”x4” pin loom to weave each day’s temperature in a houndstooth pattern before joining them altogether with a simple whipstitch.

Moore also included special markers for equinoxes and solstices (spring: bee, summer: sun, fall: maple leaf, winter: snowflake). “Especially given our rapidly changing climate, I think it would be fascinating to create an additional blanket of the Twin Cities temperatures from 2022 and a blanket from 2042 to get a a striking visualization of how things have changed in the span of 40 years,” Moore noted.

Moore’s love of data is unsurprising. He holds a PhD in mathematical biology and is currently employed as a software engineer, lending an air of interdisciplinarity to his weaving practice.

Weaving is often a generational affair, with lessons passed down and reimagined. The title of Lisa Torvik’s piece Horda 3rd Gen refers to Hordaland, a traditional district in western Norway near Bergen, known for the patterns she utilized in her weaving. Adapted from these traditional patterns, some found in a coverlet made by her own instructor (pictured below), Lisa’s weaving experiments with placement and repetition to add her own flair.

Lisa’s mentor with a coverlet based on an old piece from her own training.

Torvik’s piece uses the “transparency technique,” a method of weaving that allows light to pass through the finished product. Tiny gaps between the yarn create pockets for sunlight to pass through, illuminating the composition. Fine fibers offer an air of delicacy, while the intricate patterning captures the eye.

Torvik became interested in traditional Scandinavian weaving after a summer exchange program in Norway. Since then, she’s used this longstanding craft lexicon to create modern interpretations that stretch her artistic perspective.

In-process weaving by Torvik utilizing transparency technique

Throughout the panel, the versatility and adaptability of the weaving practice was evident. Musings about the tedious, yet meditative, act of preparing the loom sprouted grins throughout the room—a common gripe (and joy) that tied the panelists together. Although on the surface it may appear that each weaver worked in completely different modes—this discussion uncovered a much deeper, shared passion for the expansiveness of weaving and its endless possibilities.

Artists in Conversation, was part of the Weaving the North exhibition, a collaboration with the Scandinavian Weavers Study Group of the Weavers Guild of Minnesota.

To learn more about events like this one and others at the NSCA, be sure subscribe to our email list at northsuburbanarts.org/subscribe. We post updates on social media too, both on Instagram and Facebook!